News Story

A Battery Made of Wood?

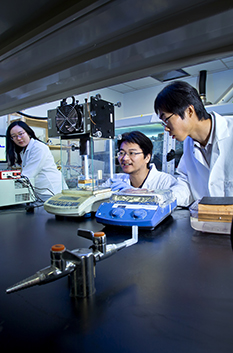

Credit:Maryland NanoCenter

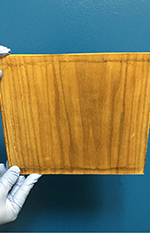

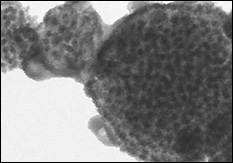

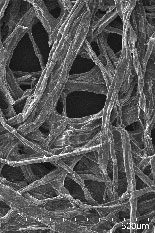

Wood fibers help nano-scale batteries keep their structure

A sliver of wood coated with tin could make a tiny, long-lasting, efficient and environmentally friendly battery.

But don’t try it at home yet– the components in the battery tested by scientists at the University of Maryland are a thousand times thinner than a piece of paper. Using sodium instead of lithium, as many rechargeable batteries do, makes the battery environmentally benign. Sodium doesn’t store energy as efficiently as lithium, so you won’t see this battery in your cell phone -- instead, its low cost and common materials would make it ideal to store huge amounts of energy at once – such as solar energy at a power plant.

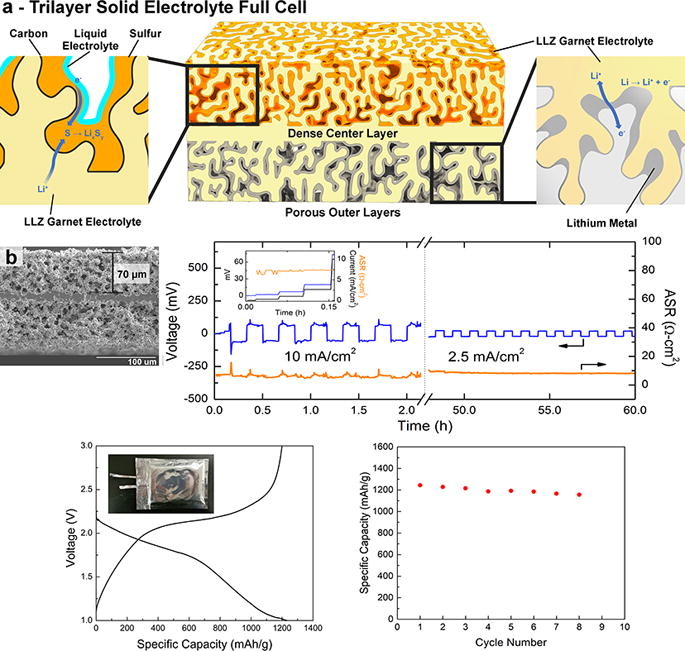

Existing batteries are often created on stiff bases, which are too brittle to withstand the swelling and shrinking that happens as electrons are stored in and used up from the battery. Liangbing Hu, Teng Li and their team found that wood fibers are supple enough to let their sodium-ion battery last more than 400 charging cycles, which puts it among the longest lasting nanobatteries.

WATCH: Author Hongli Zhu explains how trees inspired the research

"The inspiration behind the idea comes from the trees," said Hu, an assistant professor in the Department of Materials Science and a member of the University of Maryland Energy Research Center. "Wood fibers that make up a tree once held mineral-rich water, and so are ideal for storing liquid electrolytes, making them not only the base but an active part of the battery."

"The inspiration for this battery comes from trees"

Liangbing Hu, Materials Science, UMD

Lead author Hongli Zhu and other team members noticed that after charging and discharging the battery hundreds of times, the wood ended up wrinkled but intact. Computer models showed that the wrinkles effectively relax the stress in the battery during charging and recharging, so that the battery can survive many cycles. This work was done by Zheng Jia, a graduate student in mechanical engineering.

"Pushing sodium ions through tin anodes often weaken the tin’s connection to its base material,” said Li, an associate professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering and a member of the Maryland Nanocenter. "But the wood fibers are soft enough to serve as a mechanical buffer, and thus can accommodate tin’s changes. This is the key to our long-lasting sodium-ion batteries."

The team’s research was supported by the University of Maryland and the U.S. National Science Foundation.

See the full paper at:

Hongli Zhu, Zheng Jia, Yuchen Chen, Nicholas J. Weadock, Jiayu Wan, Oeyvind Vaaland, Xiaogang Han, Teng Li, and Liangbing Hu

Nano Letters, 2013

Published June 18, 2013