News Story

'They Are Playing With a Huge Fire'

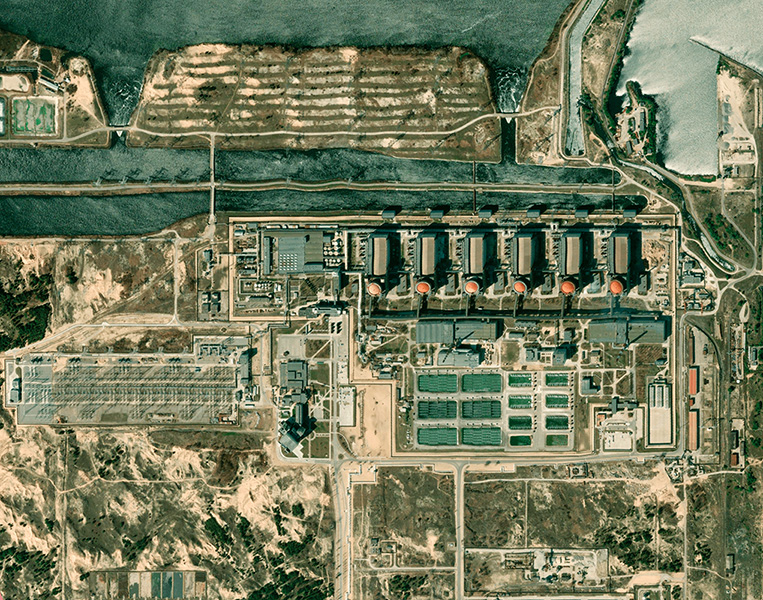

Satellite view of Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant in southeastern Ukraine. Photo by Naeblys via Adobe Stock.

While a United Nations report released yesterday called for a “safety and security protection zone” around Ukraine’s Zaporizhzhia nuclear plant to prevent a humanitarian and environmental disaster amid Russia's occupation of the plant, a University of Maryland expert in nuclear plant risk assessment said long-term global measures are urgently needed as well.

The UN and its International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) should commence an international treaty process to ban military operations around nuclear power facilities, which generate about 10% of the world’s electricity, said Mohammad Modarres, Nicole Y. Kim Eminent Professor in Mechanical Engineering and director of the Center for Risk and Reliability.

Modarres, who received American Nuclear Society’s 2019 Tommy Thompson Award for outstanding lifetime contributions to nuclear safety, has been observing months of rising tension as Russian troops dug in around the facility, which has sustained damage from fighting and retains only a shaky—but critical—connection to Ukraine’s power grid. He spoke to Maryland Today about worst-case scenarios for Zaporizhzhia, as well as why he believes nuclear power is critical to the world’s future.

We keep hearing “Zaporizhzhia is not Chernobyl,” but what does that mean?

It’s an entirely different design. Chernobyl used graphite to moderate the reactor, which caught fire and exploded during some abnormal operations. Whatever might happen here, it could not be as bad as Chernobyl, in which there was essentially a “puff,” and the whole reactor core went into the air. This is physically not possible in the Zaporizhzhia plant, which is another Russian design known as VVER-1000 and doesn’t use graphite.

Having said that, it doesn’t mean an accident won’t happen in Zaporizhzhia, especially under the current conditions.

Can you envision a chain of events leading to an accident that causes a radiation release?

That is very much possible. The worst scenario would be if the reactor is operating and loses power from the outside grid. It will automatically or manually shut down—but shut down doesn’t necessarily mean it’s safe. It keeps generating a lot of heat from the radioactive core and takes many days to cool to a point it is not going to cause significant melting in the core; so it has to have power from outside or from on-site generators during that time. On site generators can easily suffer damage from heavy shelling.

I’m less concerned about shelling of the reactor containment vessels, which are very, very sturdy. They can actually withstand an aircraft impact. The spent fuel pool is kept inside the containment vessels as well (although some might be in concrete canisters outside in the plant yard). But outside, there is a lot of auxiliary equipment needed for operation of the plant for intakes, cooling—so if there are bombardments to those types of equipment, it puts the reactor in danger of losing its cooling capabilities, and melting.

Why is even one of six reactors still in operation there? Would you begin a shutdown if you were running this plant?

Absolutely—I would not be operating a reactor in these conditions. This plant provided a high percentage of Ukraine’s electrical power, and now the Russians have apparently diverted it to their own use. I’m not a political or strategy expert, but in my imagination, they may also see this as a protective wall, which is perhaps why they have placed military equipment inside the site. They are playing with a huge fire.

Worst case, how big a radiological disaster is possible?

This would be more like what happened in Fukushima, Japan, with some areas to evacuate and decontaminate. If there were a release, the radioactive material could get airborne, and mostly irradiate people who are not very far from the reactor. Depending on wind direction, it could contaminate areas nearby and increase radiation exposure as far as 40 to 50 miles away. There is also a psychological impact that can be more harmful for some people than the radiation itself.

Some commentators have suggested that Russia is using the plant not just for energy, but to threaten Ukraine. Can a nuclear power plant be a weapon?

After Sept. 11, all nuclear plants went through a self-examination of exactly that question. Unfortunately, the answer is probably close to a yes, if there is a coordinated effort by terrorists who know the design and control of the nuclear plant. But the likelihood of this is remote, given the safeguard protocols in place. Nuclear plants don’t explode like a bomb, but if you deprive all the cooling, the reactor core melts, and if one manages to open the containment building, which is not that difficult, you can get that radioactivity into the environment and cause havoc.

What should be done about this?

This is personal, not technical, but I think nuclear plants should be protected during wartime in a way similar to how international laws against war crimes limit how you conduct a war against a population. I think now that this has happened, the IAEA probably needs to lead the development of an international treaty to protect these facilities, which can put civilians even in places that are not part of the war at risk.

Do we need nuclear power to fight climate change, or does Zaporizhzhia suggest the risks are too great?

If you think about what climate change could potentially do to humanity, to health, security and the safety of living things, comparatively, the risks from nuclear plants would be negligible. For example, let’s look at the tsunami-induced Fukushima event. Although the tsunami was not due to climate change, similar scale climate-induced flooding is possible. However, the tsunami itself killed nearly 20,000 people in Japan, and the Fukushima nuclear plants didn’t do that. [A worker exposed to radiation died of lung cancer officially attributed to the disaster, while several other cancers have been linked to it as well.]

No technology is risk-free, not even completely renewable ones like wind or solar, which can create risks, for example, to the environment during manufacturing, and also can’t completely provide the uninterruptable base electricity we need by themselves. So I am still very much in favor of expanding the use of nuclear energy widely, but at the same time providing mechanisms, international policies and other barriers against these types of events.

This story originally appeared in Maryland Today.

Published September 7, 2022