News Story

Is It Safe to Breathe Yet?

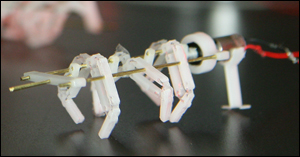

Soot oxidation.

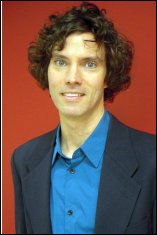

Peter Sunderland, assistant professor of fire protection engineering at the University of Maryland's A. James Clark School of Engineering, recently won a National Science Foundation Early Faculty Career Development Award to improve our understanding of how soot is formed and burned. The results of his research can show designers how to build cleaner and more efficient engines for trucks, buses, airplanes and other combustion systems, and reduce pollution that may harm our lungs and our environment.

Surprisingly, soot has been hard to study because of the complex chemistry in flames. Sunderland aims to separate experimentally two overlapping phases of soot production—soot formation and soot oxidation—so each can be more effectively analyzed and measured. This in turn will help engine designers improve the way fuel is injected and burned in engines.

Sunderland is the first to use a double-flame burner to study the chemical reactions that occur when soot oxidizes, or burns away.

"In a normal flame, like a candle, soot is formed low in the flame and burns off near the top," Sunderland says. "However there is a lot of overlap, making it difficult to measure the formation and oxidation rates. In this double flame, the upper flame has only soot oxidation, so there is no such overlap and thus the oxidation rates can be measured more accurately."

The burner has two distinct flames. The lower flame is a bright yellow hydrocarbon flame that emits a soot stream. This stream then enters the upper flame, which is a barely visible hydrogen flame. The soot chemistry in the upper flame is simpler and easier to study than in a normal flame.

Soot is made up of big carbon molecules. In some cases, soot is desirable – it is what lends the yellow color to a candle flame and it is processed into toner used in most printers. It also speeds fire growth and is a very dangerous pollutant that contributes to climate change. Soot is what colors the black exhaust emitted from diesel engines. Tiny soot particles can enter the lungs and bloodstream, leading to cardiovascular disease and lung cancer.

Both graduate and undergraduate students will help Sunderland with this new research, which will be incorporated into the courses that Sunderland teaches. He also will develop a day-long flame laboratory based on this project for high-school students. The Clark School's Department of Fire Protection Engineering has the only accredited undergraduate program of its type in the country.

National Science Foundation Faculty Early Career Development awards support and honor teacher-scholars for integrating outstanding research and education. For more information, visit the NSF web site.

Published April 26, 2010